I’ll take it as a providential sign that my writing of this post was interrupted by the election of a man who seems so clearly to embody the synthesis at which I’m driving. Praise God! Viva Pope Francis!

That synthesis, again, at which I drive is one between the concern for evangelization (i.e. the salvation of souls) and the concern for human development (i.e. the liberation of the poor). It is a synthesis that is apparently possible, as the witness of the Popes and of the African Church seem to demonstrate. Yet, for whatever reason(s), it is also one that has been notoriously difficult for the Western Church to achieve. Rather than a true unity of the two concerns, we find in her a division between those devoted to the one and those devoted to the other. In part, this situation is no doubt due to the overwhelming scope of both concerns: the world appears so spiritually lost, and poverty so intransigently egregious, that an adequate devotion to both causes seems impossible. Each is too all-encompassing to admit a rival. How can we possibly hope to attend to both? We must either assume that poverty is “not that big of deal” and attend to the salvation of souls, or assume that “most everybody will be saved” and attend to the liberation of the poor.

That is a bit of an oversimplification, but I think it encapsulates pretty well where we find ourselves today in the American/Western Church. Clearly, the dichotomy is inadequate. But we must realize that it is not going to be healed by simply asserting that ‘Faith and Justice go together’, and that ‘Catholicism is a religion of Both – And.’ True as that refrain may be, no realization of unity will come about without a simultaneous transformation in our understanding of the relevant concepts and their relationships. Whenever the Church confronts the paradoxes of Revelation, she finds herself forced again and again to re-conceive as directly proportional those relationships previously thought to be inversely proportional. Relationships of competition must be reframed as relationships of correspondence, and this necessarily involves a dramatic re-thinking of the related terms. Overcoming the crisis between Faith and Justice (E and D) will thus require a profound re-imagination of the problem and its terms: a deep revolution of the understanding of what we mean by Development (Justice), and of what we mean by Evangelization.

I would suggest that the key to this transformation lies in a much needed return to the authentic teachings of the Second Vatican Council. There, the Church clearly sought to bridge these modern divides by positing a revolutionary Christocentric anthropology, a teaching that, despite best intentions, has yet to be fully received into the life of the Church.

The mentioned divide between ‘humanitarian’ and ‘evangelical’ concerns was already much bemoaned in the first half of the twentieth century leading up to the Council, first by the Church’s enemies, and eventually also by those within her bounds. Henri de Lubac, among others, complained of an overly individualistic understanding of salvation, cut off from any sense of duty toward the human community. Individual piety and personal sanctification had been unnaturally sequestered from the natural human values of equality and justice, supplying leverage to the Marxist critique that Christianity’s supernatural hope left it uninterested in the welfare of the present world. However, De Lubac argued that this critique was based on a skewed conception of the Christianity, one rooted at once in the secularization of the human community on the one hand, and in an ‘extrinsic’ conception of the relationship between nature and grace on the other.

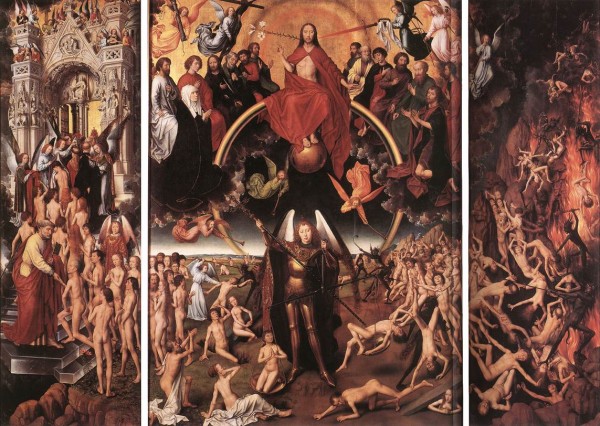

What needs to be recognized, he argued, is that the ‘humanitarian concern’ was, in fact, originally bequeathed to the world by Christianity. It is not as though such notions as ‘the universal fraternity of man’, ‘the equality of persons’, and ‘human dignity’ were widespread in the classical world before the advent of the Faith. They must rather be recognized as the mutual fruits of Christian doctrines: of Creation in the imago dei, of the universal Redemption in the blood of Christ, and of the destiny of mankind to union with God. In the first millennium of Christianity and in the Middle Ages, these ‘humanitarian concepts’ are deeply interwoven into the central tenets of the faith: human history and the human community are understood in terms of the arch of salvation history that flows from Creation and culminates in the eschatological return of Christ. There is no separation between evangelical and human concerns. Everything is united in a comprehensive vision of faith.

It is only with the modern period that we begin to see the secularization of the above-mentioned concepts. Dignity, equality, fraternity, and liberty are no longer set within an eschatological hope or a soteriological framework; they become the sole prerogatives of the secular state, quite independent of any question of an individual beliefs. Faith is here relegated to the realm of the private conscience, bearing little or no relevance to questions of justice in human society.

At the same time, and in complementary fashion, the faith begins to be articulated by theologians in such a way that the supernatural gratuity of grace was set in contrast to the immanent structures of ‘pure nature’, resulting in a rather stark stratification between the worlds of the natural and the supernatural. Faith and salvation are accordingly conceived as bearing, at best, a tangential relation to the ‘natural’ desires of human society for peace, unity, equality, justice, etc. The light of faith is certainly necessary to purify natural reason in their regard, but they are understood to possess their own immanent structures independent of any reference to Christ. Thus these concerns, once thoroughly Christological and ecclesial, are more or less ceded to the competence of the secular state.

In short, what we see emerging in the modern period is a fully secularized anthropology, an understanding of the good of man that is entirely divorced from faith in Christ, and which nonetheless retains a number of ultimately Christian values, along with a sense of history that is derived from Christianity’s eschatological hope. Thus, while rejecting the transcendent dimensions of that hope, modernity continues to envision itself as progressing towards the perfect human society of liberty, fraternity and equality. This drive culminates ultimately in Marxism’s final immanentization of eschatology: the desire for heaven is translated into the desire for a human utopia; human development is supplied with a purely ‘this-worldly’ term.

However, the appeal of this utopia depends on the prior divergence between faith and the ‘humanitarian concern’… to the healing of which divergence I hope to return in the next installment. Enough for now. In the next post I will to discuss the response of De Lubac and the Second Vatican Council to this modern crisis, with the hope of shedding light upon our current situation. Peace!